Chronicles of Modernism: uncovering the history of the Isokon Building, north London’s answer to the Bauhaus

Jake Elliott: The wall-mounted barograph suggested cold and unsettled weather in Hampstead. It was the 23rd December 1937, the streets were close to freezing, but the basement club of the Lawn Road Flats was flushed with drink and conversation, the table tops flecked with claret and brown onion soup. A ‘two-bird special’ was at the heart of the menu and Christmas pudding was to follow.

Twenty-six guests including Wells Coates, Ernst Freud, Herbert Read and F.R.S. Yorke mingled and would later recline on Aalto chairs over cigars and coffee, lamenting what might’ve been for the Bauhaus in Britain. They were hosted by Jack and Molly Pritchard, gathered at the Isobar to bid farewell to Marcel Breuer, the designer of the very room in which they sat.

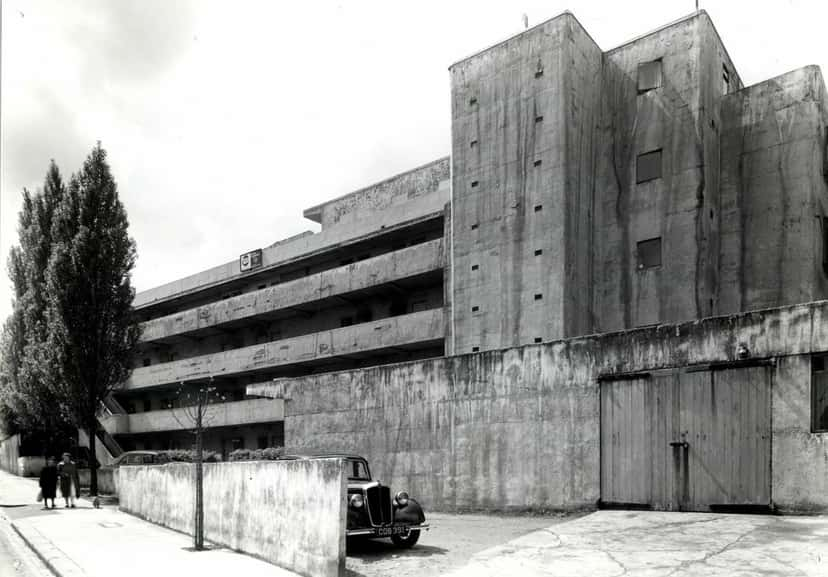

The creation of the Lawn Road Flats in the years preceding Breuer’s farewell dinner has left an indelible mark on design and architecture. The building remains a monument to the Modern Movement in England, but also to its frustration and neglect at the hands of a largely apathetic establishment.

The Lawn Road Flats were designed by Wells Coates for the psychiatrist Molly Pritchard and her husband the furniture entrepreneur Jack. For large sections of the twentieth century it was home, drinking hole and dining club to many of the world’s greatest artists, architects and writers.

Jack Pritchard met Wells Coates in their respective forays into the design and manufacture of plywood furniture in the late 20s. They quickly struck up a friendship and in the spirit of 1920s bohemian attitudes, Coates and Molly Pritchard began a romantic relationship, encouraged by Jack. In 1930, the Pritchards procured a plot of land near Belsize Park with the intention of building a pair of interlocking houses, to accommodate the complexity of their domestic arrangements: one for themselves and the other for Coates and his family. The Pritchards and Coates swiftly went into business, but funding for the scheme was hard to come by.

By 1931, the trio had achieved very little progress with the Lawn Road plot and Pritchard wrote to Coates to suggest a change in direction, proposing “unit dwellings” which could be sold with their furniture. With this development, came suggestions of a change in company name, Coates wrote to Pritchard, “Why not Isometric Unit Construction (units of same measure), ISOCON?” Over dinner at Rules in Covent Garden, the C was swapped for a K and Isokon Ltd. was founded.

Coates’s detailed plan for the flats owed a lot to the architectural developments of continental Europe. As a member of the influential Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne (C.I.A.M.) whose illustrious membership included Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Alvar Aalto, Sigfried Giedion, Berthold Lubetkin, Maxwell Fry and Ernő Goldfinger, Coates was stewed in the theory and practice of Europe’s architectural avant-garde.

Importantly, it was Molly Pritchard who drew up the concept and the brief for the Lawn Road Flats, drawing on Gropius’s notion of the ‘Minimum Flat’ delivered at the C.I.A.M. conference of 1929. Molly delivered the brief to Coates, stipulating that they reflect ‘modern lifestyles’ and were to be aimed at young working women, as well as men.

The Lawn Road Flats opened on Monday 9th July 1934. The building’s pale pink exterior popping against the bright summer sky. Guests were invited to the roof terrace for cocktails and canapés and in a nod the streamline profile, MP Thelma Cazalet broke a bottle of beer against the façade, launching the building into the world.

The rush to complete the project on time resulted in lots of teething problems for the first residents, but the flats were a success with the mainstream and architectural press. Walter Gropius moved in on 18th October that year and became Controller of Design for The Isokon Furniture Company. Marcel Breuer and László Moholy-Nagy followed shortly after.

Hospitality was quite literally at the core of the Lawn Road Flats. Among the many services offered to residents (shoe-cleaning, laundry, bed-making), a dumb waiter ran down the spine of the building, delivering freshly cooked meals to residents from the in-house kitchen. Jack Pritchard was an enthusiastic host and while these services supported the concept of the flats as a machine-à-habiter, he was keen to create a vibrant society around the Lawn Road Flats. In September 1937, the occupants received a letter from Jack, who was living in the penthouse with Molly, informing them of his decision to open a club in the basement for the tenants and their friends.

Jack asked Marcel Breuer to design the basement space which would be known as the Isobar. The restaurant was to open out onto a outdoor deck and was furnished by Breuer with some of his most famous pieces for the Isokon Furniture Company. In another nod to the British obsession with the weather (the initial allusion in the name ‘Isobar’) Breuer installed a barograph in a glass case under a blown-up picture of some clouds.

The bitterly cold night of Breuer’s farewell dinner in December 1937 was to be the last service run by Tommy Layton, the pioneering resident chef who procured rare and interesting beers for the Isobar members. He was replaced by Philip Harben, a flamboyant and charismatic cook who would go on to become one of Britain’s first television chefs. At Lawn Road, he was renowned for his adventurous cuisine, as well as his charisma, ostentatiously claiming that he “could scramble eggs and make mayonnaise long before [he] could read Thucydides or solve a quadratic equation.”

Harben presided over elaborate dinners in aid of increasingly political causes, such as a ‘a week of Spanish food’ in 1938 (attended by Louis MacNeice and Henry Moore) the proceeds of which were donated to the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief. A ‘bowl of rice’ dinner was similarly held for the China Campaign Committee and invitations were sent to prominent left-wing figures including R. H. Tawney, Megan Lloyd George and Harold Laski.

This combination of radical architecture and politics, alongside adventurous cooking proved to be irresistible for many of Hampstead’s local artists. Regular exhibitions were held in the Isobar and the basement transformed itself into an informal north-London salon, regularly attended by Adrian Stokes, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Naum Gabo.

Where the artists went, the critics followed, Nikolaus Pevsner and Herbert Read came, ate and drank, while Modern Movement architects were often found propping up the Isobar, particularly Erich Mendelsohn, Serge Chermayeff and of course, Wells Coates. Publisher and poet Francis Meynell recalled members were “all word-wise, as well as food-wise.” These genteel cultural pleasures, created jointly by chef and clientele, resulted in a long waiting list for membership at the Isobar right up until war broke out in 1939.

Jack Pritchard sold the Isokon Building to the New Statesman magazine in 1969 and the Isobar was promptly converted into flats. It was sold on again in 1972 to Camden Council and fell into a state of disrepair, before it was subjected to a sensitive restoration by Avanti Architects, lead by architect John Allan.

The re-vamped Isokon Building opened in 2004 with 25 flats for key-workers on a shared ownership basis and 11 for private ownership. Understandably, in a city with such a pronounced shortage of housing, the Isobar was not re-instated, but the Isokon Gallery Trust has overseen the conversion of the former garages into the Isokon Gallery, an exhibition space which tells the story of the building, its residents, the Isobar and the Isokon Furniture Company.

–

Last year, we met Tom Broughton, founder of Cubitts and penthouse resident, for a look at life on the top floor of the Isokon – watch the film here or listen to the podcast here.