Photo Essay: Corinna Dean’s guide to 20th-century rural architecture, Slacklands 2

It’s been five years since Corinna Dean, architecture lecturer and founder of the ARCA, Archive for Rural Contemporary Architecture, published Slacklands, a guide to 20th-century rural architecture in Britain. Her exploration into the gritty, less-than-bucolic rough edges of the British countryside surveyed – with a respectful, unjudgmental eye – everything from a bomb-proof artillery tower in the middle of the Thames to Torness Nuclear Power Station.

Her second book, Slacklands 2, available now, builds upon and extends the remit of the previous edition to encompass a wider array of architectural typologies, as well as a selection of international examples. In addition, the artist and illustrator Peter Nencini has contributed a series of interpretations on a selection of the buildings to accompany Corinna’s photography, while architect Charles Holland takes over from Margaret Howell as writing the foreword. Here, we share a selection of images from Slacklands 2, as explained by Corinna.

Curtis’s & Harvey Ltd Explosives Factory. Cliffe, Medway, UK

“Curtis’s & Harvey Explosive Factory covers 128 hectares of marshland near the Kentish village of Cliffe on the Hoo Peninsula. The history of the site was laid down when a small-scale gunpowder storage facility was set up in 1892, then acquired by Curtis’s & Harvey Ltd who established a new chemical explosives factory. During the First World War it became a government-controlled establishment manufacturing a range of propellant and blasting explosives.

“The enterprise was short-lived, closing in 1920 due to the post-war reduction in the demand for munitions. The layout of the First World War phase of the explosives factory survives largely as earthworks, concrete foundations and a few standing buildings. Most of the buildings from this phase have been demolished or reclaimed for reuse, leaving behind a complex of concrete floor slabs, protective earthwork traverse (blast protection mounds), embanked earthen tram-beds and narrow drains.

“By 1931 all of the former factories on Cliffe Marshes were under the ownership of the current owners, the Port London Authority and, apart from the occasional limited military activity during World War Two, the land has been untouched, save for use as grazing marshland. Some of the factory structures have been removed in more recent times as a result of the relocation and rebuilding of the sea wall in the 1980s.”

Olau Passenger Ferry. Sheerness, Isle of Sheppey, UK

“On the north-west tip of the Isle of Sheppey lies Sheerness, where, just below its 19th-century Garrison Fort, sits the Olau Passenger Ferry at the meeting of the Thames and Medway rivers.

“Its covered walkway clad with corrugated sheeting sits on a concrete footing, with inverted trusses, and the structure is barely weathered. The ferry opened in 1974 when the Danish company Olau Line started a car/passenger ferry service from Sheerness to Vlissingen in the Netherlands and from Copenhagen to Aalborg, Denmark.

“In 1977 Olau attempted to start a service from Sheerness to Dunkerque, but lack of demand meant that by the end of the 1970s the company was heavily in debt and in 1979 Ole Lauritzen was forced to sell 50% of the Olau Line to the West Germany based TT-Line.

“The terminal at the Port of Sheerness plays a significant part in the Isle of Sheppey’s economy. Covering more than 1.5 million sq m, it is one of the largest foreign car importers in the UK, as well as handling thousands of tonnes of fruits from all over the world (stacks of Chiquita banana containers line the port front). Inexpensive land and good infrastructure, including a rail network that branches off the main passenger line, have attracted industries to the port area, including producers of pharmaceuticals, steel, sausages and even garden gnomes.

“The abandoned Passenger Ferry Terminal stands as a symbol of the varying fortunes of a major port and the changes in patterns of trade, tourism and of naval warfare, power and strategy.”

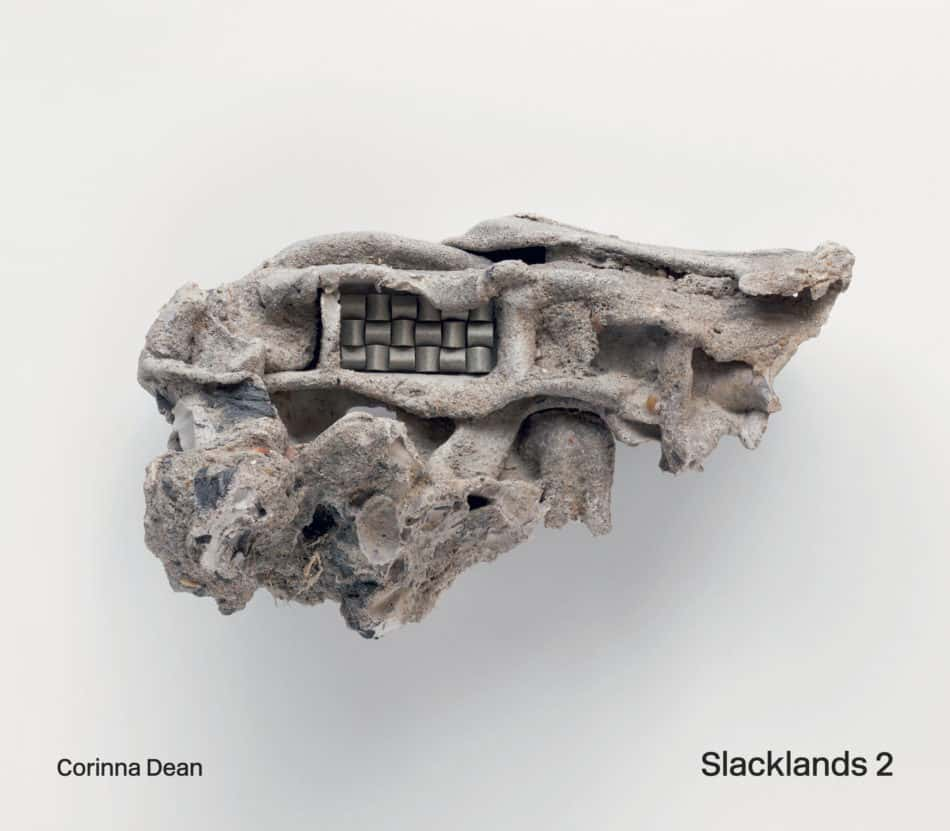

Pillbox in Former Monastic Building. Minsmere Marshes, Suffolk, UK

“The Pillbox inserted into the ancient archaeological ruin in Minsmere Marshes, near Saxmundham, appears a parasitic intrusion into what has been described as a significant piece of Suffolk’s medieval history. However, on closer inspection, the concrete pillbox provides structural support to prop up remains of Leiston Chapel, a form of mutualism where a symbiotic relationship between buildings is created.

“During World War Two Minsmere was one of the key defence sites on the Suffolk Coast, sitting on what was described as the ‘coastal crust’. To protect the coast from German forces a management programme of artificial flooding on what was previously agricultural land was introduced. In June 1940 the sea sluice was opened and the gate allowing the exit of freshwater from the river closed. When the whole area was flooded the sea sluice was closed and the area remained inundated until 1945, when the operation of the sluices returned to normal.

“Sitting on the hillock above the Minsmere marshland is the former monastic building, situated in the centre of what was originally a Premonstratensian Abbey, an order of canons founded in France in 1102. Leiston Abbey was founded in 1182 near Minsmere, by Ranulf de Glanville, Lord Chief Justice to King Henry II. Fearing an increased risk of flooding, the monks abandoned the abbey in 1363 and a new complex was built further inland by Robert de Ufford, Earl of Suffolk.

“John Ette, an ancient monuments inspector for Historic England, confirmed its status, ‘This is of great archaeological importance, being the early site of the Leiston Abbey and where the monks created their community before they were inundated by coastal processes. The concrete pillbox and machine-gun emplacement were inserted into the eastern end of the structure. At the highest point in the landscape and with a building already offering the potential for camouflage, the hillock was an obvious site for a strong point.’

“The medieval walls of the chapel act as a shell for the rectangular concrete pillbox that was built within the structure and provided with numerous firing points for infantrymen.”

Headframe of the Sainte Marie Coalmine. Ronchamp-Comte, France

“The Ronchamp Coal Mines covered a huge area located in the Vosges and Jura coal mining basins, in eastern France. Operating for more than two centuries, from the mid-18th century until the mid-20th century, they profoundly changed the landscape, the economy and the local population.

“The Sainte Marie Coalmine sits on the road leading up to Le Corbusier’s Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut, just outside the small town of Ronchamp. The Roman Catholic chapel was the last piece of architecture completed by the architect before his death in 1965 is said to be a masterpiece of sculptural qualities. The building makes up one of 17 of Le Corbusier’s UNESCO listed sites.

“The Sainte Marie Coalmine was one of the major Ronchamp mines and was worked intermittently between 1866 and 1958. The concrete headframe was reinforced in 1924. On 29 March 2001, the headframe was listed as a French National Historical Monument.

“The Sainte Marie shaft closed permanently in 1958 and was filled in with schist, a coarse-grained metamorphic rock which consists of layers of different minerals, with shale and topped with a concrete slab. It had been planned that the headframe should be demolished, but because of strong community attachment to it as part of their local heritage, it was saved in 1972 by a local resident, Dr Marcel Maulini, who went on to establish a museum of mining in Ronchamp.”