Photo Essay: a global tour of mid-century modern houses

In this Photo Essay, Phaidon Press share a selection of

images and accompanying descriptions of six houses selected from their new Atlas

of Mid-Century Modern Houses by Dominic Bradbury. From the USA to

Australia, these six homes survey how the influential architectural movement

played out across the world, including one example, White Fox Lodge, which we

sold this year.

“The mid-century period was, without doubt, a golden age of

architecture and design. It was a time of optimism and imagination, full of

ideas and ingenuity, which still resonates with us today. A whole series of

powerful influences and currents converged, catalysed by a post-war consumer

boom, encouraging architects and designers worldwide to experiment and innovate

as never before. House and home were radically reinvented and remade during the

Fifties and Sixties, as modern lifestyles evolved to embrace more informal, playful

and open-plan living patterns.

“It is no exaggeration to say that the way we live today is

grounded in the ideas formulated and refined during the mid-century era. Many of

the key themes that we associate with contemporary living were explored and

perfected during the post-war period – including inside-outside connectivity;

multipurpose living spaces; the rise of the kitchen as a family hub; outdoor

rooms; and the adoption of fluid, interconnected rooms rather than ‘landlocked’

dedicated circulation routes.”

Ses Voltes, Raimon Torres and Pierre Colin Cala Carbó, Sant Josep, Ibiza, Balearic Islands, Spain, 1964

Raimon Torres was the son of the pioneering modernist architect Josep Torres Clavé, who died during the Spanish Civil War. Born and educated in Barcelona, Torres followed his father’s example and went on to collaborate with Josep Lluís Sert and Erwin Broner, among others.

In 1961, soon after graduating from architecture school,

Torres moved to Ibiza and spent 15 years living and working there as well as

documenting the island and its buildings as a photographer, with its vernacular

fincas (farmsteads) serving as a key subject. Torres’ work of the

Sixties included several houses that sought to be both contextual and contemporary

at one and the same time. Perhaps the most successful of these was Ses Voltes

at Cala Carbó to the west of the island.

Here, traditional materials and references splice with modern

forms, as bare stone meets whitewashed concrete. The residence sits on a rugged

hillside and faces the ocean, including a series of striking rock formations

jutting out into the water. Service spaces are pushed to the rear, which is

more enclosed than the rest of the house, while the dwelling opens up to the

vista via a series of terraces and verandas.

Thredbo Ski Lodge, Harry Seidler, Thredbo, New South Wales, Australia, 1962

The ski resort of Thredbo came of age during the late Fifties and Sixties. Situated in New South Wales’ Snowy Mountains, it was developed by the Lend Lease Corporation from 1957 onwards and is now one of the region’s most popular alpine resorts, with over a dozen lifts and more than fifty runs. Harry Seidler – a keen skier himself – was asked to design a ski lodge by Dick Dusseldorp, the head of Lend Lease at the time. The lodge was positioned on a hillside looking across to the ski slopes, and alongside a mountain creek.

Sitting on a stone-walled base level, the rest of the timber-framed house cantilevers outwards by degrees as it reaches storeys two and three. The ground floor is devoted to the entrance, stairwell and utility spaces, including a boot room, with the surrounding terrace sheltered by the projecting floors above. Mid-level holds the bedrooms, with balconies to two sides of the building. The upper level hosts the main living spaces, which have the best views but also flow out to the uppermost balcony, supported by five triangular wooden trusses thrusting outwards into the void. Seidler’s ski lodge references many ideas commonly seen in traditional mountain chalets but gives them a distinctly modern twist.

Schaefer House, Marquis & Stoller, Napa Hills, California, USA, 1969

Architect Robert Marquis was born in Stuttgart and emigrated to America in 1937. He studied architecture at the University of Southern California and co-founded a San Francisco-based practice with Claude Stoller and associate Peter Kampf in 1956.

The 1969 Schaefer House was, essentially, a cabin perched in

the Napa Hills, modest in scale and plan but engaging in its design and

execution. The cabin sits on the brow of a slope, accessed to the rear by a

simple wooden bridge. This leads into a covered walkway that runs through the

building and connects with an elevated balconied deck looking out across the

undulating hills. A key element of the timber building’s pleasing character is

its roofline, largely a monopitch parallel to the slope but with a slim,

secondary element over the service spaces running down to the rear.

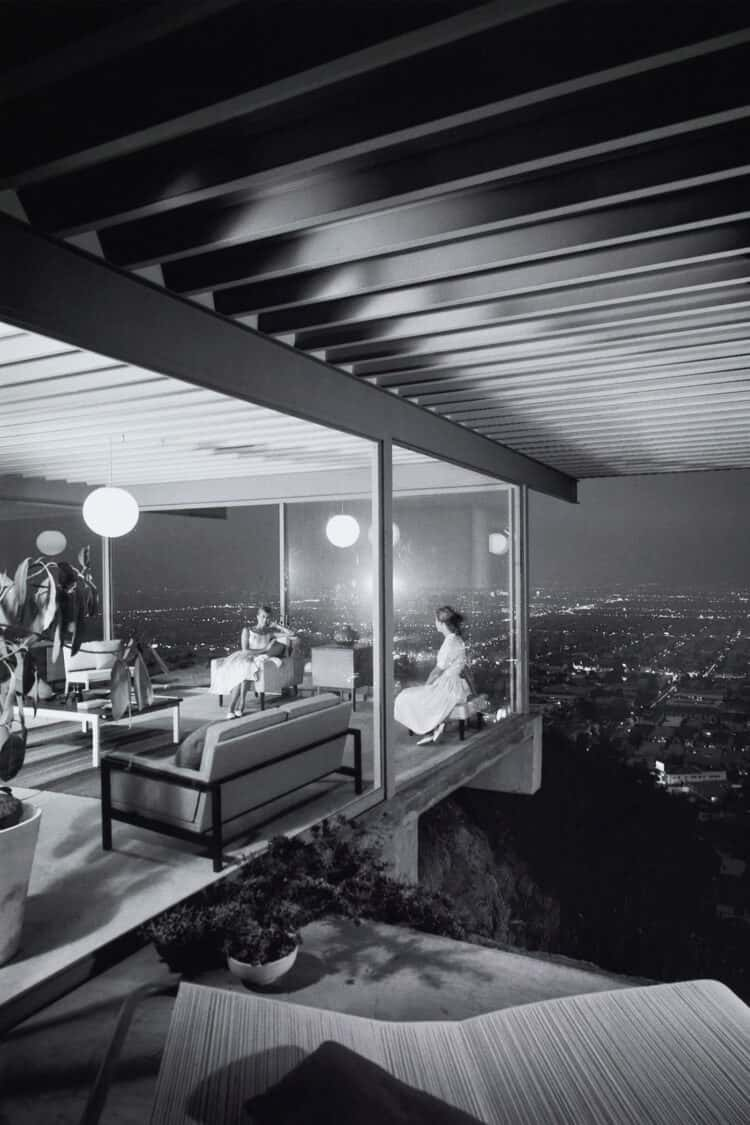

Berkeley House, John Dinwiddie, Berkeley, California, USA,

1947

John Ekin Dinwiddie came from a family of Bay Area builders. His father

established a construction company in the wake of the San Francisco earthquake

of 1911, with the business expanding at a fast rate. Dinwiddie studied

architecture at the University of Michigan and worked briefly with Eliel

Saarinen. He settled back in San Francisco and established his own practice in

1931.

This house in Berkeley, from 1951, was a commission for the architect’s sister-in-law. It sits on a prime hillside site looking out over the waters of the East Bay and across to the city of San Francisco itself.

Dinwiddie placed the main living spaces at the heart of an L-shaped plan, with the floor-to-ceiling windows connecting to the veranda and the vista. A two-storey element sits to one side of this central zone and holds the majority of the bedrooms, also facing the Bay views. The building was restored and updated in 2016

by Olson Kundig Architects.

Kaufmann House, Richard Neutra, Palm Springs, California, USA

This most famous residence in Palm Springs – and, perhaps, all California – is the great exemplar of ‘desert modernism’. With the Kaufmann House, Neutra took the relationship between inside and outside space to a new level of intimacy, dissolving boundaries through multiple means. The rugged beauty of the mountain backdrop and the desert ‘moonscape’, as he called it, serve to enhance the impact of its horizontals and verticals. It was a project for department-store magnate Edgar J Kaufmann, who had commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to create Fallingwater a decade before.

The Palm Springs house was intended for winter use only, and

was moulded to Kaufmann’s needs. Neutra designed a home of stone, steel and

glass around a central, sandstone chimney that anchors the living/dining

pavilion. Other spaces radiate from this central point in a pinwheel formation,

connected by covered walkways and that include a guest pavilion and

service/staff quarters.

Floor-to-ceiling glass in key parts of the dwelling links house and garden, including a glazed wall in the living room that sinks down into the floor, creating a seamless flow to the adjoining terrace and onwards to the swimming pool. While the majority of the house is single-level, Neutra also created a ‘gloriette’ on the roof- a semi-sheltered belvedere that features louvred walls and its own fireplace.

White Fox Lodge, John Schwerdt, Udimore, Rye, East Sussex, England, UK, 1965

White Fox Lodge has been described as John Schwerdt’s magnum opus. The architect trained in Brighton and worked largely in Sussex and the south of England, with heritage and conservation projects forming a key part of his portfolio. But he was also influenced by modernist architecture – particularly, the more organic approach advocated and pioneered by Frank Lloyd Wright, whose work was a key point of reference in the evolution of White Fox Lodge. The dwelling is located in the Sussex village of Udimore, a few miles inland from Rye and the coast, and was commissioned by Sidney and John Horniblow.

Schwerdt and the clients sought close synergy between the house and its setting, including landscaped gardens designed by Sylvia Crowe. The floor plan of the single-storey home adopts a pinwheel plan, as seen in the work of Richard Neutra and others. A central entrance hallway features an internal, glazed courtyard devoted to a fountain and pond. From here, four wings radiate outwards, with two housing the key living spaces and the other holding bedrooms for the family and guests. Each wing of the house – which is made principally of white-painted brick – features carefully placed banks of floor-to-ceiling glass that look across the meadow and out into the landscape beyond.

Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Houses is published by Phaidon, £100 Phaidon.com