Peter Bogaczewicz on the tension between natural and built environments

Peter Bogaczewicz has been photographing natural and built landscapes for over a decade. As part of our ongoing collaboration with British Journal of Photography, the photographer and architect discusses the roots of his interest in the contradictory subjects and his unique approach.

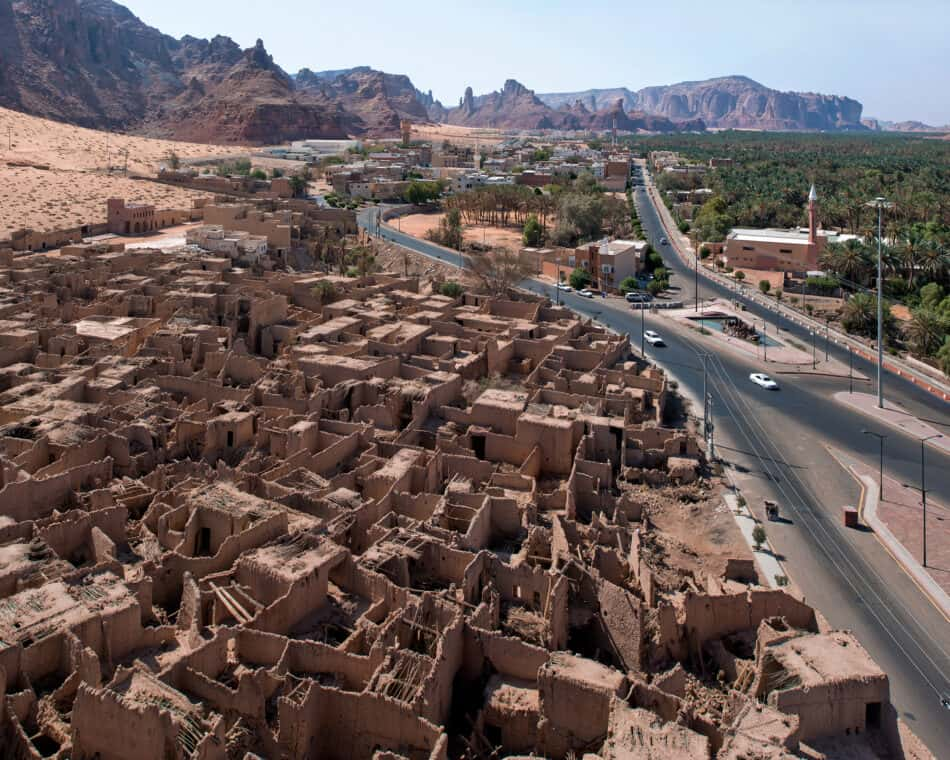

From the coastal landscapes of Canada to the deserts of Saudi Arabia, Bogaczewicz’s sweeping photographs investigate the relationship between nature, the built environment and the human connection with both. Informed and complemented by his architectural background – Bogaczewicz divides his time between the two disciplines – the resulting images explore how humans interact with their surroundings, leaving temporal traces on the landscape.

Most recently, the Canadian photographer has turned his attention to the Arabian Gulf, where human activity has left prominent marks. Glass buildings, luxury malls and affluent neighbourhoods have emerged out of stretches of warm sand, interrupting the ancient landscape. Exploring this contemporary space with his camera, Bogaczewicz investigates the juxtaposition between organic and manmade environments. But this tension is multifaceted too, drawing on the contrasts between history and progress; memory and the present; nature and culture.

Here, Bogaczewicz tells us about the similarities between his work as an architect and photographer, his particular interest in the Arabian Gulf and the ever-complicated relationships humans have with the natural world.

What made you want to become both an architect and a photographer?

As a child, my family moved around a lot between Europe, Africa and North America. In those early years, I witnessed how different places have distinct qualities. It wasn’t a rational realisation, just a child’s appreciation of how one place felt different to another. Over time, I became more conscious of this, and of how places can be further transformed through architecture.

Photography has always been a complementary activity. With both, I strive to engage in a conversation with the environment, but of course, the process is different. Architecture is a constructive process: an idea is formed into something that didn’t exist before. Photography is reflective: an idea is distilled from its surroundings. It is less of an invention and more of a commentary. In my work, I find these disciplines overlap; the goal of producing a clear response to the environment – one that is inevitably visual, spatial and responsible – is becoming more aligned.

In what ways does your work explore the relationship between nature, the built environment and their human connection?

The natural environment figures prominently in my work, but human activity is what activates the scene. What interests me most is the interaction between the two, because that speaks to the ever-complicated relationship we have with nature. On the one hand, we cherish it and make a comfortable home in it; on the other hand, we destroy it. These seem like polar opposite notions, but increasingly, through our actions, they are intertwined.

How did your interest and work in the Arabian Gulf develop?

It began during a visit to Saudi Arabia more than a decade ago, while I was working as an urban planning consultant. I was struck by the uniformity of the landscape: its warm, monochromatic tones of sand and stone characterise the whole expanse of the Arabian Peninsula. At first glance, it seems monotonous, but I found the unexpected and subtle diversities within it infinitely interesting.

Much of it looks uninhabited and untouched, but whenever one sees any visible human intervention, it jumps out. I was fascinated by how clearly and consistently it presented itself throughout the wider landscape of Arabia. Focusing on the gulf became a way of honing in on a greater environment that has become associated with a modern attitude to transforming the terrain. This is where the contrast and tension between the natural environment and its occupants become dramatically pronounced.

In your work, there is a tension between the natural landscape and built structures, but also between history and progress; memory and the present; nature and culture. Is this something that you consciously explore?

The tension depicted is multi-faceted, and although specific to the regions photographed, it is inevitably a constant that presents itself to various degrees in all inhabited places. I’m interested in history; sometimes, in an almost anthropological way, I try to put the present in the context of the past by making references to what was and what has become. Similarly, it is interesting to examine how a culture has evolved and developed a particular way of interacting with nature.

To what extent do you think the built environment influences the way we experience the world around us?

It plays a critical part. The built environment is the counterpart to the natural environment. One, or a combination of the two, inevitably constitutes our constant surroundings. We cannot disassociate ourselves from that. But the built environment is not so much the opposite of nature; more accurately, it is a reorganisation of nature to suit our needs. In that sense, the built environment is something that we need in order to understand the world around us, be it our natural surroundings or our social structures.

Discover more at peterbogaczewicz.com