Bauhaus Centenary: we mark 100 years of the school with a look at its British legacy

In the most literal sense, the Bauhaus was a solely German endeavour. First opening its doors to students in Weimar in 1919, the school subsequently moved twice: once to Dessau in 1925 and then to Berlin in 1932, shortly before its closure by the Nazis in 1933.

But, ironically, the forces that determined its termination in Germany prompted its propagation abroad. Figureheads like Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer and Josef and Anni Albers all fled to America or elsewhere in Europe – with many stopping off in Britain – bringing with them their brand of clean-lined, beautifully simple architecture for a modern age.

To mark 100 years of the school, we’re looking at its British legacy. The Modern House has had the privilege of selling many homes designed by Bauhaus faculty members over the years, and we are always struck by the enduring livability and lasting aesthetic appeal of the school’s residential output. Here are some of the best.

Sea Lane House, East Preston, West Sussex

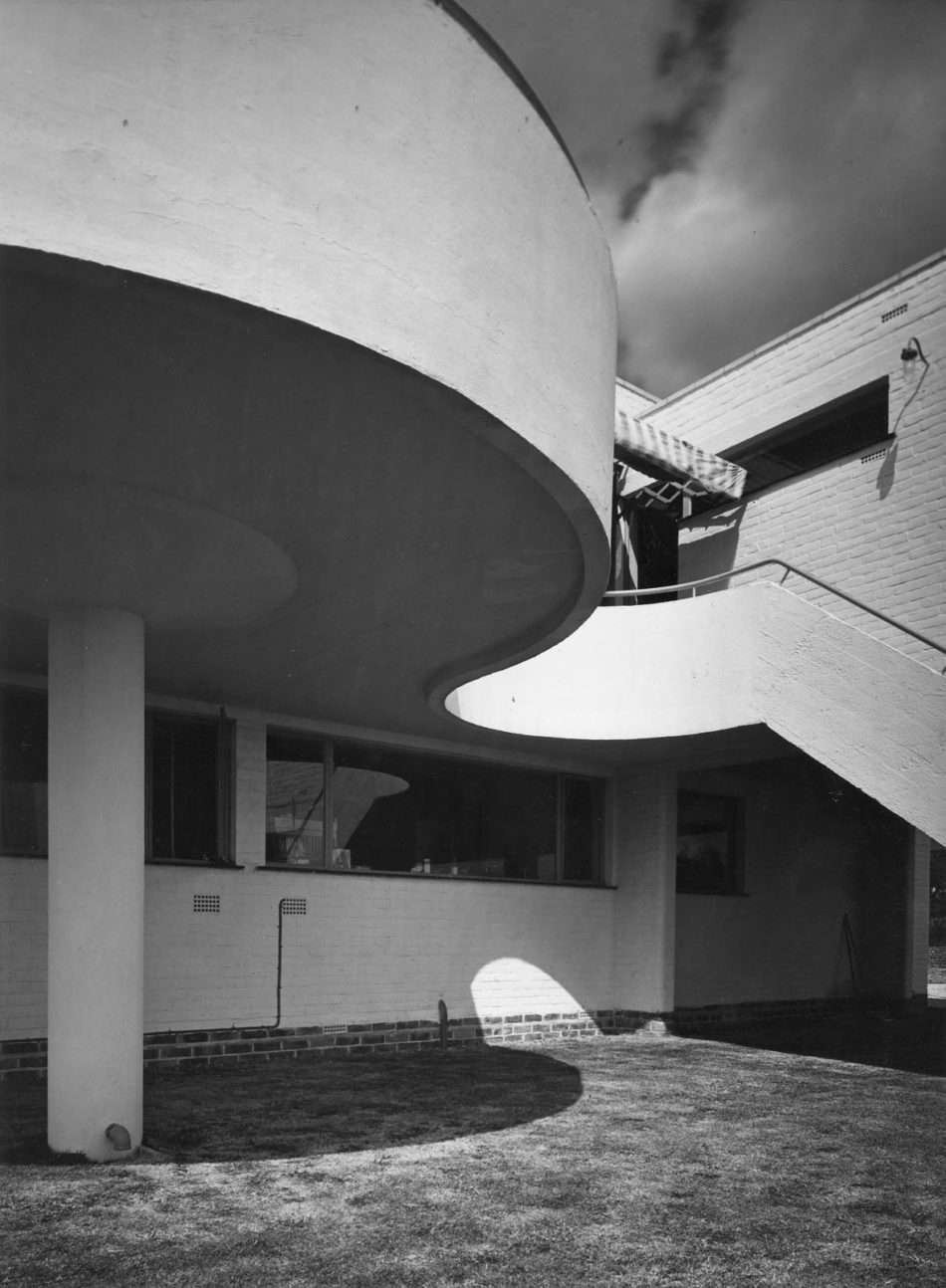

Breuer arrived in London in 1935, where he lived for two years. During that time, he contributed his only surviving pre-war building in Europe, Sea Lane House, with the help of British architect F.R.S. Yorke.

While largely orthogonal and graphic in its distinctive L-shaped profile, the house’s design also includes a curved sun terrace on the first floor. The expressive nature of the design marks a shift from the more rigid geometry that defined the Bauhaus’ early years.

Last year, our team had the pleasure of staying at Sea Lane House as part of an in-house initiative, Field Work.

Isokon Building, Lawn Road, London NW3

Where did the Bauhaus émigrés call home when they came to London? Gropius, Breuer and Laszlo Maholy-Nagy, headteacher of art at the Bauhaus, all found themselves at home – both physically and intellectually – at architect Wells Coates’ Isokon Building, the pinnacle achievement of inter-war British Modernism.

Completed in 1934, the Isokon expresses the fundamental Bauhaus concept of a Gesamtkunstwerk or ‘total work of art’, which encouraged a holistic treatment of architecture, furniture and interiors. As such, the 32 flats all had built-in plywood furniture and were designed to be as comfortable as possible, prompting architectural critic J.M. Richards to call them “more like the machine-à-habiter than anything Le Corbusier ever designed”.

Maresfield Gardens, London NW3

Austrian-German architect Hermann Zweigenthal arrived in London in 1935, joining other Modernists like Coates, Maxwell Fry and Yorke at the MARS think tank.

As a friend and colleague of Gropius – who invited him to teach at Harvard in 1940 – Zweigenthal drew from Bauhaus principles in the design of this house at Maresfield Gardens in Hampstead, which was completed in 1938. The exterior is defined by simple geometrics, asymmetrical glazing and painted steel balustrades, while the interior design prioritises natural light and connection to the gardens.

Ladbroke Grove, Notting Hill, London W11

The Bauhausian contribution to British architecture didn’t just come from the Germans, at least not in whole. British architect Edwin Maxwell Fry was aided by Bauhaus founder Gropius on the design for Number 65 Ladbroke Grove, a Grade II-listed building in Notting Hill.

The building stands as one of the best Modern Movement buildings in London, and articulates many of the fundamental Bauhaus architectural principles: clean lines, lack of superfluous ornamentation and generously proportioned, light-filled spaces.

Halsbury Close, London HA7

The German architect of this house, Rudolph Frankel, may have told Gropius he was too busy to join the Bauhaus faculty, but his engagement with the school’s teachings is hard to deny, as this house in Stanmore illustrates.

Many of the hallmarks are here: a clean, crisp silhouette, linear strips of Crittall glazing and a spatial design that accommodated modern living.