Best in Class: The Modern House’s dispatch from Alvar Aalto’s house and studio in Helsinki

This summer, The Modern House visited Helsinki, for a trip characterised by architectural sightseeing, design store shopping and saunas. One unequivocal highlight emerged: that of Alvar Aalto’s house and studio.

As a prolific and masterful architect, Aalto is the undisputed doyen of Finnish, even Nordic, Modernism. First establishing his studio in the early 1920s, Aalto’s architectural practice produced an eclectic oeuvre that spans the styles of Nordic Classicism, Functionalism and the International Style.

But to prescribe Aalto’s projects as being examples of ‘x’ style is to deny the idiosyncratic architectural language he developed throughout his life. Like any true great, Aalto is considered as such because of his clarity of individual expression, uniqueness of design and uncharted experimentation.

Nowhere is that more evident than in his furniture, textile and lighting designs, of which the simple, almost naïve-looking ‘60 Stool’ and the curvaceous ‘Paimio Chair’ – named after the tuberculosis sanatorium for which it was designed – are perhaps the most famous. They serve as perfect distillations of Aalto’s greatest achievements: functionalist utility, bentwood innovation and sculptural elegance.

The Aalto House, which was completed in 1936, lies in the suburb of Munkkiniemi, a 20-minute drive from central Helsinki. The architect designed the two-storey structure together with his first wife, Aino, in a process that was evidently tricky: “I’ll tell you, it is easier to build a grand opera or a city centre than to build a personal house,” he later said.

The street-facing exterior of the house is defined by two distinct volumes: a residential wing clad in stained-timber slats, and a white-washed brick section, which hosted Aalto’s studio until 1955.

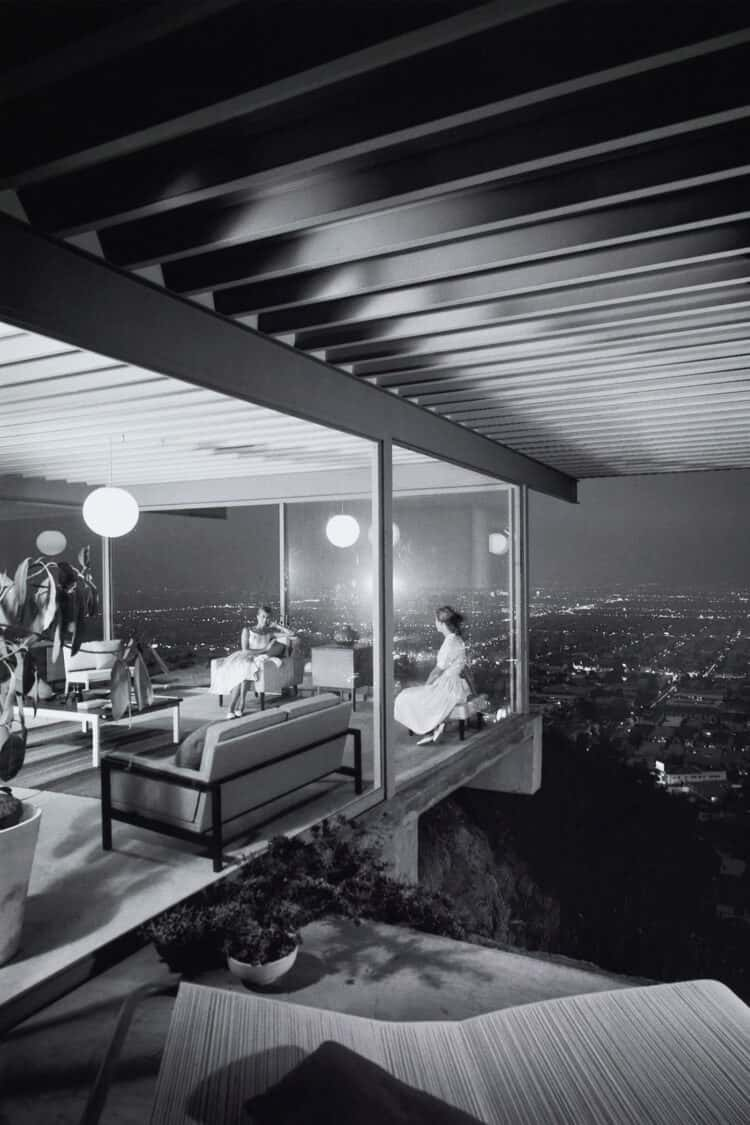

The stark severity of the front of the house is in contrast with the rear elevation, with its south-facing terrace on the second floor and large picture windows. In fact, the house is defined by contrasts, from the garden fence, which delineates the perimeter of the plot half in brick and half in wood, to the relative openness of the ground floor compared with the more modestly-sized bedrooms upstairs.

As an example of Aalto’s move away from Functionalism towards an interest in organic forms and romanticism, the house deploys details such as Japanese-inspired sliding doors, jute wall cladding, freestanding fireplaces and a healthy amount of joinery to comprise a cosy, intimate space.

Aalto’s practice ramped up in the 1950s, with a number of high-profile public commissions demanding more desk space than could be found at his house, and so a new studio was designed a short walk away.

The resulting building turns its back to the street, in the same vein as the house, to seem rather unassuming when approached from the road. A walk around the back of the house reveals Aalto’s masterful demonstration of architectural surprise: the design centres around an inner courtyard, laid out as an amphitheatre, concealed by the inward-facing structure.

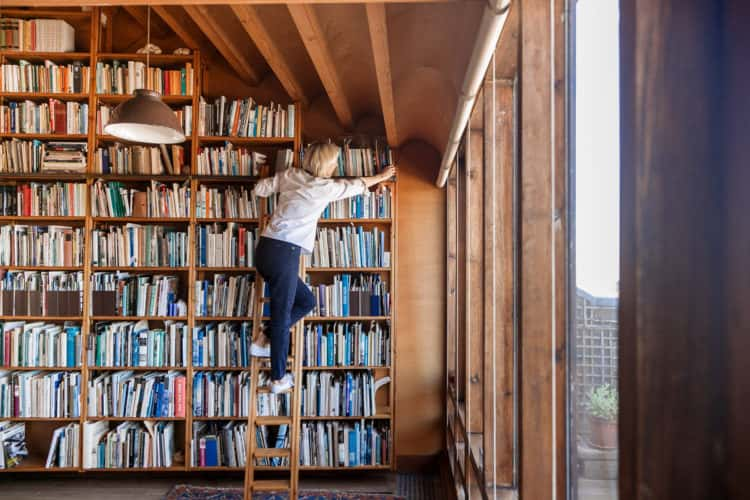

Inside, the main office space sits under a pitched roof, with celestial windows feeding light down onto generously-sized desks. Vines growing up the exterior fulfil Aalto’s intention to establish a connection with nature.

Occupying the curved wing of the floorplan is a studio space, decked out in Aalto’s lighting pendants, bentwood furniture and architectural models, along with Berber rugs, high-reaching vines and white walls. It’s a photogenic space, and one of calming harmony; a clear and holistic realisation of Aalto’s vision.

The building was extended in 1963 to comprise a canteen, which Aalto like to refer to as the ‘Taverna’. While he headed-up the office until his death in 1976, he banned all work-related conversations in the canteen during lunch. To sit in the modest space with this in mind is to understand Aalto’s ethos at its most powerful: one of human focus, in which unobtrusive design aids rather than dominates people’s lives.

Read more: The Modern House visits Helsinki